LOOKING AT MUSIC PUBLISHING DEALS

Reviewing the Intersection of Music, Finance, and Law

Let’s jump right into it.

If you subscribed to ‘Spin the Block’ and are wondering why you got this email, it’s because I’m writing here now; and for those who have been tracking, so far, we’ve covered Record, Management, and Producer and Songwriter Deals; and now we’re going to get into Music Publishing Deals. In this article, we’ll cover:

music publishing;

the intersection of finance and the music business; and

music publishing deals

PUBLISHING

What is music publishing? “music publishing” or “music publishing royalties” are royalties, and the management of royalties, that are generated from the composition of a song. The composition is the portion of the record attributable to the writers and composers (producers) of a song, as opposed to the sound recording (or master), which is typically owned by the primary artist or record label.

Publishing royalties primarily include:

Mechanical Royalties - royalties paid to the rights holders of the composition whenever a song is physically bought, downloaded, or streamed;

Performance Royalties - royalties generated and paid to the rights holders of the composition whenever a song is performed publicly and in live performances, publicly broadcast, and digitally or terrestrially played on radio;

Synchronization Royalties - royalties generated and paid to the rights holders whenever a song is “synchronized” with an audiovisual production - think when you hear a song during a movie or commercial.

I’ll cover music royalties, in detail, in another article, but as an example of how complex it can get, look at this breakdown of mechanical royalties from Law.com:

“In its simplest form, if a service were ad-supported, the rate would be the result of taking the greater of a specified percentage of the digital music service’s revenue and a specified percentage of the costs to the service of licensing the master recordings containing the compositions (e.g., primarily payments to record companies that own and/or control the masters that are referred to as Total Content Costs or “TCC”), then subtracting the amount of money that the service is paying for public performance rights (e.g., payments to the performing rights organizations such as ASCAP, BMI, SESAC and GMR). The result would be the income pool for mechanical rights that would be shared by all compositions streamed by the service according to the number of streams on a composition-by-composition basis.

Note if the offering is a subscription-based service as opposed to an ad-supported service, a per-subscriber penny rate royalty (e.g., $0.60, or $1.10 depending on the type of offering) multiplied by the number of subscribers for a particular service is introduced into the calculation of whether the TCC percentage is used or the subscriber royalty rate is used (which formula prescribes that the “lesser” of the two amounts be utilized).

With respect to the starting point of the royalty calculation, the percent of service revenue rates initially established by the CRB start at 15.1% in 2023 and increase on an annual basis until it reaches 15.35% in 2027. To be more specific, the rate for 2024 will be 15.2%, for 2025 15.25%, for 2026 15.3% and for 2027 15.35%. The percent of service TCC is set for all offerings, other than a bundled subscription offering, at 26.2% for the five-year period from 2023 through 2027…”

Simple enough, right?

Music publishing is an expansive topic that can’t adequately be covered in one article. This is simply an overview, but here’s a good book to read if you’re looking for somewhere to start.

I’m not high; my eyes just look like that.

“They eyes hide, they eyes high;

My eyes wide shut to all the lies”Jay Z, ‘Caught Their Eyes’

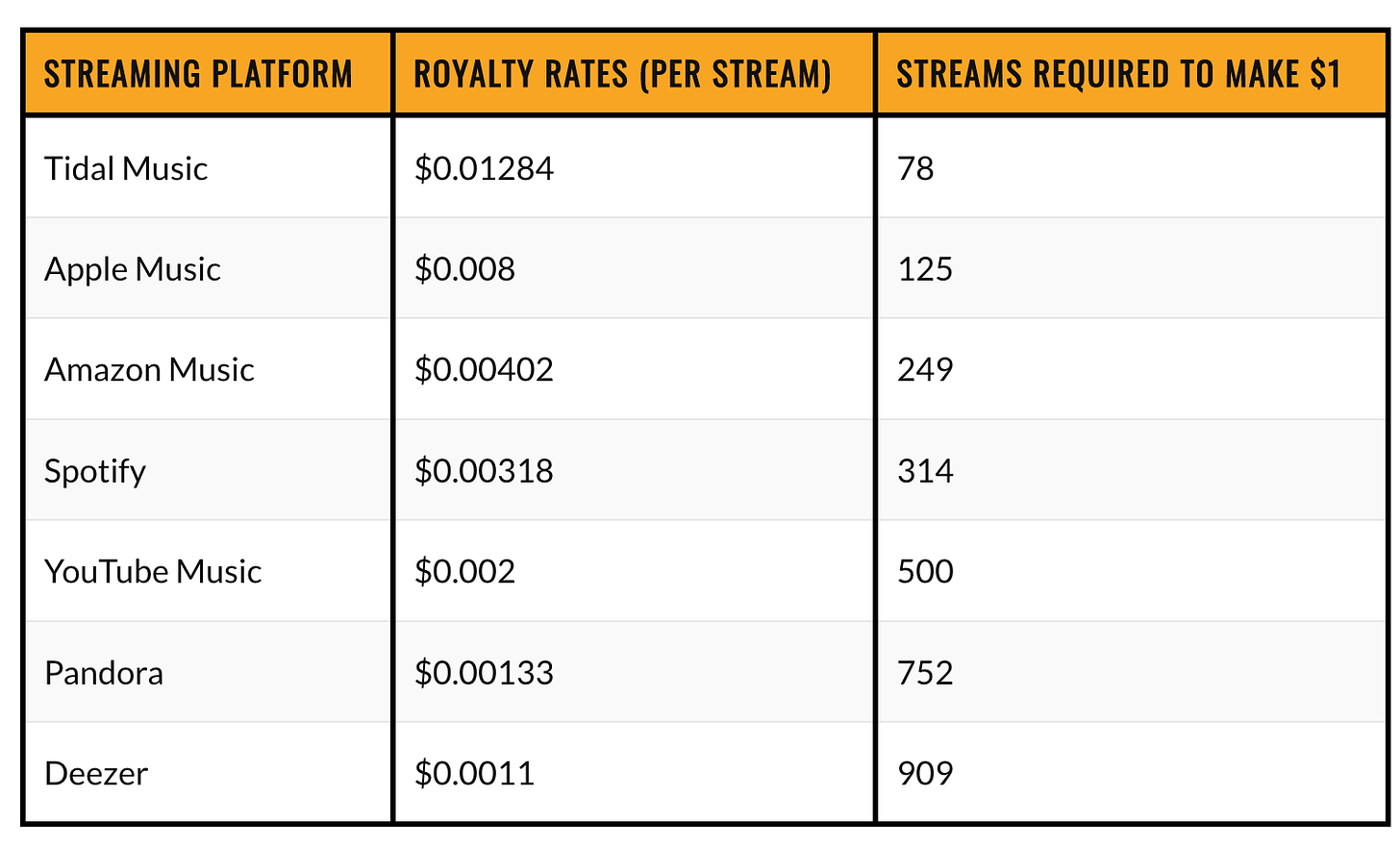

For the purposes of this article, you can expect streaming income to show up in your royalty/financial statements something like that chart above:

Keep in mind, however, that as Law.com complicatedly stated, mechanical royalties payable to writers and producers will be ~15% of those royalties. This means that, as a writer and producer, if a song generates Spotify royalties at the $.00318 per stream rate, then the composition would generate roughly ~15 cents per 314 streams; and this isn’t taking into account instances where there are multiple writers and producers on the record.

Also, keep in mind that these royalty rates will vary because they’re largely determined by the music streaming company’s revenue and “then shared by all compositions streamed by the service according to the number of streams on a composition-by-composition basis.” Essentially, it’s a pooled model rather than the fan-powered royalty model utilized by Soundcloud.

In addition, different countries pay different amounts. As Ditto Music, a music distribution company, states in their article, listeners in the US will pay somewhere around “$0.0039 per stream, while listeners in Portugal will only pay $0.0018”.

As you can see, this part of the music business is not glamorous and is data and finance-intensive. There’s an old music business quote that says music publishing is a “nickel and dimes business.” For that reason, before we get into the particulars of the deal, I want us to zoom out and look at the intersection of music, finance, and law, particularly as it relates to music publishing.

This will help us understand why these topics are important.

CHANGING OF THE GUARD

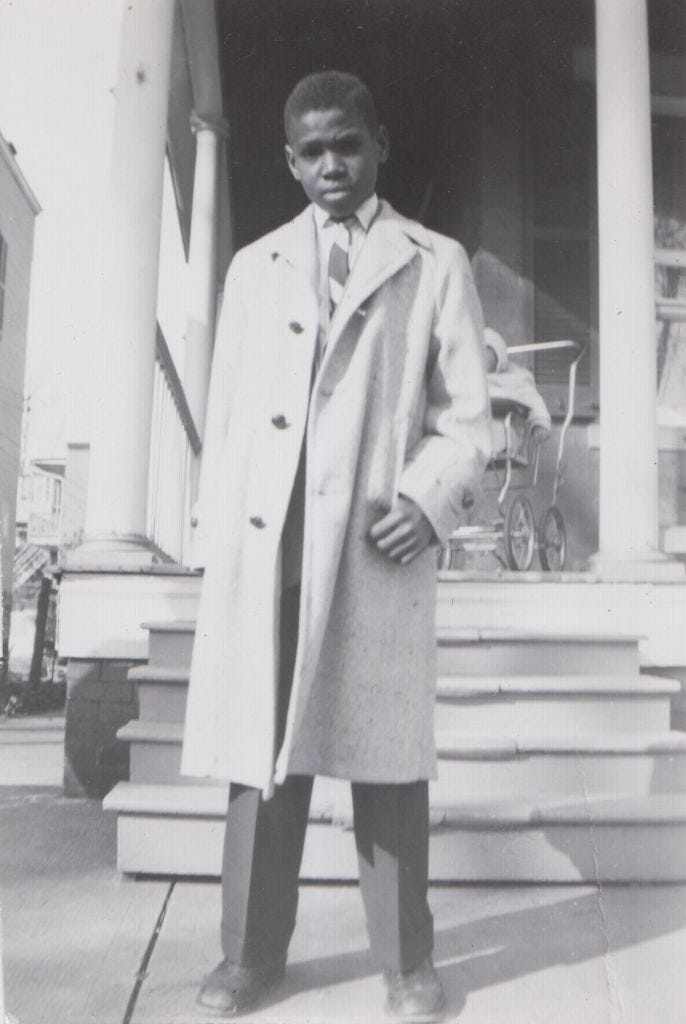

Photo of Reginald Lewis, as a youth, the first black man to build a $1B business when he acquired ‘Beatrice International Foods’ from ‘Beatrice Companies’ for $985 million in 1987 in a private equity acquisition.

Many people are talking about the recent acquisitions in the music business made by private equity firms such as Shamrock Capital’s $300 million acquisition of “Taylor Swift’s first six albums for around $300 million from a group including Ithaca Holdings, a media holding business led by famed music manager Scooter Braun and a portfolio company of The Carlyle Group”; as well as partnerships between traditional private equity firms/professionals and celebrities like Kim Kardashian, who recently “launched a private equity fund, ‘Skky Partners’, which she co-founded with Jay Sammons, a former partner at the investment firm Carlyle Group”; much of this momentum has been built from the success of her apparel company, Skims, which has now “raised $270 million in a new funding round that values it at $4 billion.”

Many other private equity transactions are happening at the intersection of media, entertainment, and finance, which I’ve covered before and will continue to cover, but, in my opinion, this is all a natural progression. One of my personal sayings is, “If we create it, we should own it.” If someone has the talent to create a product or service - and they know what to do, then they should own it. Simple as that. It doesn’t mean they have the skill set to manage every function, but if they’ve proven product-market fit, then they should be put in position to lead that function. They may just need the training, exposure, and information… like every other human being.

The point is although we’re publicly seeing more music x private equity deals happen, private equity and financial engineering have largely always been a part of the recorded music business. This is why ownership is important. If you don’t own anything, then you’re at the mercy of the charity of those who do; particularly whenever these financial transactions happen.

What is fairly new, however, is the emerging confluence of multiple trends:

many entertainers, celebrities, and media professionals are gaining outsized influence;

technology is democratizing traditionally close-gated sectors;

there is increased transparency around the financial returns (or the lack thereof) of institutional investors and their investment managers; and

investment firms are aggressively seeking new investment opportunities, whether emerging, overlooked, or growth markets.

The trick, though, is it starts looking a lot like colonization if the creators and entrepreneurs in those markets don’t understand the game and position themselves to lead.

Let me leave that alone.

So how does private equity touch the music business?

Corporate Mergers and Acquisitions - The first way private equity touches music is through traditional corporate structures and corporate M&A activity, whether through institutional or venture capital investment; the latter, which is “a form of private equity and a type of financing that investors provide to startup companies and small businesses that are believed to have long-term growth potential.” An instance of where private equity showed up in corporate mergers and acquisitions was in the City of Coral Springs Police Officers’ Pension vs. Block Inc. case, which I covered here. Other instances may include companies that are capitalized for the purpose of addressing the recorded music market.

Catalog Acquisitions -

Contemporary Acquisitions: Increasingly, and due to the emergence of music streaming, music catalogs have been seen as viable alternative investments. This is due to the predictable revenue, and royalty, streams which can be calculated based on an artist’s streaming income, in addition to other royalty revenue sources. This has led to large catalog acquisitions by private equity firms. Here are a few examples:

HarbourView Equity Partners acquired half of Nelly’s music catalog, presumably his publishing, for a reported $50 million;

Hipgnosis Songs Capital “acquired 50% of Rick James’ publishing interests, writers’ share, neighbouring rights (Sound Exchange) and recorded masters (UMG) share of income in his catalogue comprising 97 songs”;

Justin Bieber, also recently “sold his entire back catalog of music — more than 290 songs — to Hipgnosis Songs Capital, the music rights investment company” for north of $200 million.

Bowie Bonds - The view of music as an alternative asset is not a new one, however, and has been seen in the past, most notably in the case of Bowie Bonds. ”Bowie bonds were first issued in 1997 when David Bowie partnered with Prudential Insurance Company and raised $55 million by promising investors income generated by his back catalog of 25 albums.”

Large Music Companies - Last but not least, private equity’s influence can also be seen in large publishing and music companies; and the deals executed between these companies and artists.

Concord Music - Concord Music is one of the largest publishing companies in the world and “owns or administers more than 600,000 copyrighted musical works and represents the catalogs of Benny Blanco, Sammy Cahn, Phil Collins, John Fogerty, Cyndi Lauper, Rodgers and Hammerstein and Ryan Tedder”.

Concord is “majority-owned by a pension fund, Michigan Retirement Systems, that has invested more than $1 billion into the music company.”

This means that the deals signed by these artists, and others signed to private equity-backed publishing companies, actually represent private equity investments in artists as companies; and artist catalogs as assets.

Founders are Artists, remember?

Imagine being an artist, and your high school teacher who didn’t think you would make it is earning his retirement money from your catalog.

I like that.

MUSIC PUBLISHING CONTRACTS

All this is important to understand when we evaluate the publishing agreement, particularly the Financial Pillar. Ultimately, (many) artists create music for the sake of art and as a creative expression, but in the music business, music is an asset with monetary value. This value ultimately sits at the center of music deals and should be understood by all parties at the table because the influx of capital into the music business through the vehicle of “deals” is a signal that institutional investors and investment managers perceive the growth potential and profitability of artists and their music.

Now, let’s get into the terms of the deal. As usual, we’ll look at this through the '3 Pillars Framework’. I’ve covered quite a few terms in my past articles, so I’m going to pull what I think are the most notable points for the purposes of this article.

Operational

In considering, it’s important for writers and producers first to ask and answer a few questions:

why do I want this deal?

what will the finances help me accomplish?

how will I utilize the finances?

have I positioned advisors and team members to help me execute my financial plan?

do I have a plan and/or team in place to assist me in continuing to advance my career strategy?

do I have a career strategy?

For many, these are basic questions; but many potential multi-million dollar enterprises were destroyed simply due to a lack of diligence in this area.

“Or what king would go to war against another king without first sitting down with his counselors to discuss whether his army of 10,000 could defeat the 20,000 soldiers marching against him?”

Luke 14:31

As we look to negotiate a publishing deal, one operational factor will be the type of publishing deal you’re signing.

ADMINISTRATION DEAL

In a publishing administration deal, the publishing company is primarily responsible for collecting publishing income and clearing requests to sample or utilize your record. You’ve seen how complicated calculating royalties can be; by utilizing digital technology and international relationships and partnerships, publishing companies can determine (if they’re good) the proper amount you’re owed; without you having to do the calculus or chase people down yourself. Additionally, there’s usually no, or minimal, investment (e.g., advance); and, as a result, pub admin companies will typically take a 10% - 15% range commission. This is really a financial term, but I’m including it here to make the point.

Many artists will sign these deals at the early stage of their careers to have a partner who can help them collect, or artists with sizable incomes will utilize these deals when they do not necessarily need a large cash-inflow, do not want to give up any ownership rights or interests to their catalog.

As Randall Wixen states in ‘The Plain and Simple Guide to Music Publishing’, “another advantage to an administration deal is that the period of time is variable and short. . . typically, administration deals are two or three years in length”.

CO-PUBLISHING DEAL

A co-publishing deal is a joint rights participation deal. You’re signing a deal in exchange for a cash advance on uncollected past and/or future publishing royalties, and, in exchange, the company will take an increased percentage of those royalties for a longer period of time. The publishing company is projecting, based on your current status and royalty estimations, how much you’ll earn. Remember, this is a private equity transaction.

The main benefit is the advance, but these deals also come with somewhat of a promise that the publishing company will help to connect you with writers, producers, and artists - though in practice… these publishing companies have hundreds of artists, and hundreds of thousands, sometimes millions, of songs to manage; and so the service level you receive really depends on the company and how hot you are as an artist, writer or producer.

TERM

By way of term length, you may see something like this:

“An initial period plus one option period, each extending for 3 years from commencement, save that each period may extend for up to 2 additional years each if the Writer’s account is unrecouped at the end of the first 3 years of the period in question”.

This means that the writer/producer will be signed for a set initial term, perhaps somewhere between 3 - 7 years (or however long the publishing company thinks it will take to recoup their advance), after which the publishing company will have the right to extend the contract for additional years; three in this example. The kicker here is that the additional option usually comes with a guarantee of another advance. That’s great; however, if the publishing company doesn’t recoup the second advance, they have the right to extend the contract for an additional 2 years in addition to the right to, first, extend the initial period by 2 years.

Again, this is a private equity transaction. The publishing company isn’t giving you this money out of the goodness of their heart, because they necessarily like your music; or even think it’s a contribution to society. That might be part of it, sure, but at a core level, the company is investing in your asset because, ultimately, they believe they will make their money back from that investment; not just for themselves but also for their shareholders.

Financial

Let’s talk money.

Royalties

In terms of the percentage collected by publishing deals, it can be straightforward. Under an administration deal, you’ll see the flat percentage we discussed, of perhaps 10% to 15% (sometimes as low as ~5%). For Co-Publishing deals, you may see a chart of royalty participation that reads something like this:

Mechanical - 70%

Publisher Procured Covers/Co-Writers - 65%

Synchronization Licenses - 70%

Publisher Procured Synchronizations - 65%

Performance Royalties - 50%

Other - 70%

This breakdown represents the percentage that the artist will receive from these different revenue streams. These numbers may be less, for the artist, depending on the artist's position, and, of course, the artist only receives these royalties after the publishing company recoups any advance.

Advance Options

Coinciding with the royalty provisions, and the option provisions discussed in the Operational Pillar section, you’ll also see advance provided for those options.

This will often appear as increases in your previous royalty rate and advances. The increase in advance will often be provided in the form of a minimum and maximum guaranteed advance. For example, if you were provided an advance of $250,000 under your initial term, you may see the following as an offer for the option period:

Minimum: $300,000

Maximum: $450,000

This is to provide you with a logical reward for being picked up for another option, but also to hedge the bets of the publishing company, limiting how much they’ll have to invest because…

It’s a private equity transaction.

To that point, and as much as possible, you’ll want to incorporate data in your negotiations. It’s easy to say, “$200,000 is more than $150,000, so let me ask for that,” or “the publishing company taking 40% is better than 50%”; and that kind of negotiation is important, but I think, particularly with the software and technology now available, these negotiations should be based in facts more than feelings. This kind of approach is not always immediately available to artists, nor perhaps needed at all times - but, to me, this is the optimal approach. That way, even if you’re asking for more than the data says you’ll recoup, at least you have a baseline of what you should be asking for.

LEGAL

In previous articles, I discussed the legal terms that apply to these contracts, so I won’t rehash them. That said, two important clauses to understand are the retention period and ownership or reversion rights.

RETENTION PERIOD

Although many publishing deals will have an initial period of a few years, followed by one or two options for more years, there will be a retention period during which the publishing company has the right to exclusively collect royalties from the songs provided and created during the term of the publishing deal. This clause, at a high level, may look something like this

“Writer shall assign copyright and similar rights to [Publishing Company] in the Compositions for the Term (initial period plus option(s)) followed by a retention period of 10 years”.

The thinking here, again, is that this is a private equity transaction. The publishing company has data and financial teams who have calculated how long it might take them to recoup the investment they’re providing. If they’re investing $500k in a publishing deal, only collecting for 3 years is probably not enough time to recoup their investment, especially since it can take months to over a year to collect certain performance and mechanical royalties.

OWNERSHIP AND REVERSION

It will also be important to determine, in your publishing deal, whether you’re being asked to assign ownership to the publishing company completely or whether your rights in your catalog will revert after the retention period. Trust me, this is important. Unless you’re selling in a large acquisition, go for the reversion. More on this in the next article.

CONCLUSION

The purpose of this article was to provide an overview of music publishing deals, which namely refers to the collection and administration of publishing interests in and derived from the composition of a record (getting paid from writing and producing records). In my next article, I’ll cover some additional music publishing topics I didn’t get to cover here. That said, if you read the Randall Wixen book, you’ll be ahead of 90% of people in the music business... at least as far as music publishing is concerned.

The purpose of this article was also to display the intersection of music, finance, and law. School and certain traditional systems teach you that everything is siloed when, in reality, everything is connected, and it’s being able to zoom out and clearly see the playing field (or battlefield, whichever metaphor you prefer) that allows you to focus and navigate correctly.

At the end of the day, there is no building that says “MUSIC BUSINESS” on the side.

That doesn’t exist.

But if you feel like I feel, then keep going.