LOOKING AT RECORD DEALS

An Overview of Recording Agreements and Negotiations

I wrote an article last year, around this time, called ‘Artists are Media Companies’; now on PAPERWEIGHT - which essentially talks about my views on the opportunity that many artists, creators, and so-called ‘influencers’ have in today’s media economy; namely, the opportunity to build brands around the influence they attain regardless of the degree of that influence. This can be seen at a basic level with social media and social media profiles, and the opportunity to gain thousands or millions of “followers.” The difference is “followers” often don’t mean a whole lot, a fraction of your social media followers will meaningfully contribute to your bottom line, you don’t own those platforms, and in many cases, you might actually be working for those platforms.

Here’s an example from the Terms and Conditions of an AI company, which shall not be named, which says that the AI company “may” use the content you upload to help them improve their app.. while you get paid nothing.

But in the words of Tupac, it could be a “fair xchange”; but only if you play it right. We all get used to a certain degree; just make sure you get what you want from the deal.

But that’s another article.

In this article, I’m going to be talking specifically about recording agreements. It’s easy to say, “Artists today can become as big as HBO!” Yeah, maybe.. but what are the odds, and how do they foreseeably get there?

*crickets*

Alright, that’s where I come in, and will attempt to shed light on in this article; at least, as it relates to the music business. The problems in the music business have been discussed ad nauseam, through movies, “where are they now?” documentaries, social media gurus, and frustrated artists alleging that they’re in slave deals. But one of the biggest problems to me is that even if you’re in the 5% to 10% of artists who break through and become a superstar, that bad contract you signed 10 years ago, or that bad team you’re with now, can stifle your ability to pivot into more lucrative enterprises.

So, in this article, I will break down a few points that artists, and labels, should be aware of. As discussed in this article, I’ll look at this through my ‘3 Pillars’ framework.

Let’s get into it:

SMOOTH OPERATIONS:

The Operational Pillar helps us understand why we want this deal, how this deal will help us reach our goals, and what we need to do to get there. When you look at a recording partnership, whether you’re on the artist or label side, it’s important to analyze what will be done.. in reality.

It’s kind of crazy to me that people think simply signing a piece of paper will lead to riches.

Three P’s:

People

Plan

Paper

Don’t just look at the paper; also look at the people and the plan. Who are the people? What are they doing now? Tangibly, and in reality. Whatever they’re doing now will transfer to you, the paper, and the results you see. Whether this is the artist who doesn’t put in the work for themselves, expects everyone else to do it, and simply wants to be famous; the manager who has no idea what they’re doing or talking about; the independent label owner who “knows people” and has a few dollars to throw into this side venture; or the major label A&R whose job might not be there in six months and is merely looking for short term streaming numbers to secure their job and their company’s market share.

It’s important to understand these things and set expectations within the contract of what can be expected from all parties. This will be brief:

Services

As a standard, most recording agreements will have some sort of services clause that states that the label will act as the distributing company of record. It will coincide with their rights to license or own the music; and further detail that they will work to commercialize, monetize and sell the music, often with additional words like “throughout the universe” and “in any medium now known or hereafter devised.”

Heavy.. especially if it comes with the words “in perpetuity.”

What it often doesn’t mention is the plan for this distribution and monetization. Both the artist’s and label’s teams should work to hash and craft this. Every artist is different, and the results can be dismal when you apply template plans to different artists.

Marketing

Depending on the type of deal you sign, the label or production company will also be responsible for marketing and the payment of marketing services. Yay, money for marketing! ..right? Well, not so fast. How will you be marketed? How will you market the artist? Do you understand the brand, or is that something you want someone else to determine for you? A label can throw money at the wall for marketing, but unless the artist and their team understand their brand and have insightful campaigns and strategies to connect with their audience, any dollars you throw at the wall will be wasted. I’ve been in those meetings, and I’ve seen some of the marketing strategies; it’s often the same thing, over and over, for album rollouts:

record the album,

tweet and post selfies and studio shots,

shoot a video,

post clips of the video,

make some gifs and lyric videos, I mean assets, and post them on Youtube and socials,

try to get press coverage and podcast interviews,

blah blah blah

This template rollout is what Drake and 21 Savage mocked with their latest album release.

The point is, figure out exactly what the label will do for you; make them explain the plan - and understand whether it works for you. On the label side, explain your requirements of the artists, and if they don’t seem to have their heads on straight, then reconsider whether it will work. Sure, you might make a few dollars, and if you’re going to own their masters, then it might not even matter; you’ll move on to the next artists when they act bad - but I like to be in business with people for the long run, and this is how you do it.

MANAGING FINANCES:

All of the pillars are important, but none cause as many headaches as the Financial Pillar, especially when it comes to music deals. This is because the parties are often not aligned in terms of expectations and who brings what to the table. Artists often feel like there’s only one of them and the label needs them more than they do, and labels often feel like there are a thousand artists who they can sign, and that the artist is not bringing anything other than their voice and maybe a few dance moves.

This all causes problems down the line when perhaps the dreams and promises of stardom didn’t quite work out, or the artist succeeds big. There often weren’t clauses negotiated closely enough to determine what happens if things didn’t work out (legal pillar); or what happens if the artist exceeds expectations. Oftentimes, this is because many label agreements are standard, pulled off the shelf, and vetted by a company’s financial team, who analyzes the company’s budget, financial projections, business models, and commitments - and understands that the company has to meet certain financial expectations; particularly when the company is a public company and has reporting obligations.

Lawyers, oftentimes, also have templates that they pull off the shelf and give to artists to sign.. as I mentioned, in my last article, “You don’t get what you deserve; you get what you negotiate. To be clear, this doesn’t just occur in music. I once had a brief chat with someone on LinkedIn who was upset because they had invested in a company and wanted to understand its capitalization and how much preferred stock the company had, in addition to the preference schedule (for another article). The lawyer at the company apparently didn’t send this. The person didn’t realize that that was something they could have negotiated before investing in the company. You see this a lot in business. People want to get into an opportunity, and they feel like they want something, but they may get intimidated because of the size of the opportunity, or maybe the other side has a high-profile lawyer who makes them feel like they’re asking for something unreasonable. To me, that never made sense. It doesn’t matter if you have the biggest lawyer if he tries to sell me a pencil for $1 million; I’d tell him to kick rocks. Always be willing to walk away.

So, how can you negotiate this, and how does that usually happen?

Advance

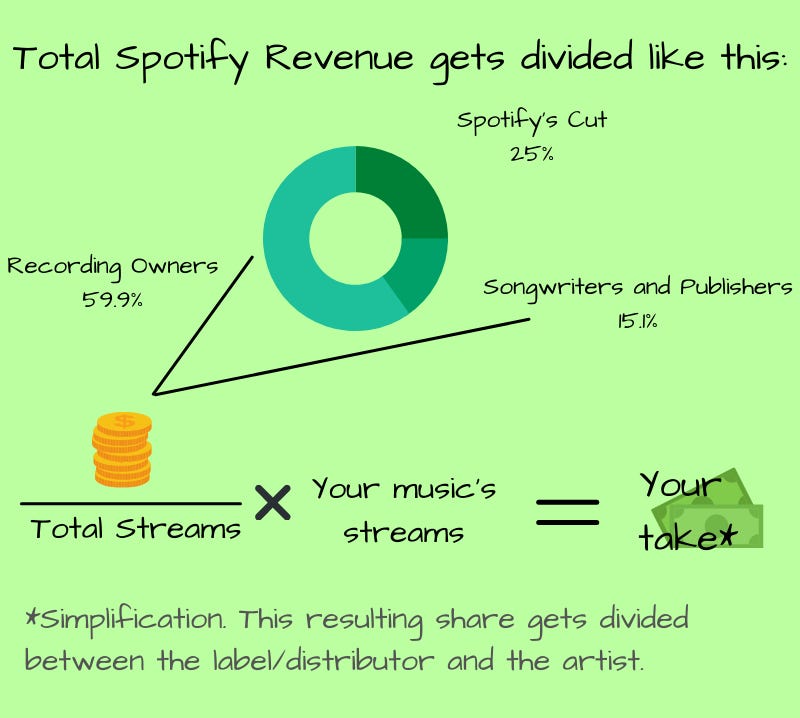

This is probably of most interest to artists, “how much am I getting paid?” Artists need to understand that the advance is a loan, yes, but it’s also (or should be) tied to the projection of what they will make in return. In the words of the late, Bankroll Fresh, “it’s all there”. If I’m a label, and I’m giving you a $200k advance and providing a budget for music production, video shoots, marketing, and other ancillary funds, it’s because I’ve (or should have) analyzed how much you’re making now (or how much I believe you’ll make) and have calculated my ROI. Many artists have dreams of $1m advances. To bring that down to reality, 1 million streams on Spotify nets you around $4 - 5k; you do the math. And if someone does give you close to that much money, think about how much you’d have to give in return.

Royalties

This gets complicated, and I’ll cover it in a different article. but the main thing to know is that there are different types of royalties in the music business. These royalties emanate from the two forms of copyright: (1) sound recordings, aka ‘masters’; and (ii) the underlying composition. These royalties are generated through sound recording, mechanical, public performance, and synchronization royalties. I’ll dive into these in depth in another article, but it’s important to know that the lion’s share of royalties come from sound recordings (masters). The point is, as an artist, you’ll want to understand how much you could be getting and do the calculation. You also need to understand who’s getting paid; are you signed to two or three labels, or are you only signed to one? That matters.

On the label side, it’s important for you to do the math as well and understand whether the deal you’re offering makes sense. Can you, realistically, see a return from the artist’s streams alone under the offered terms? Are you prepared for the event that recoupment takes longer than expected? Or might you also think about building in contingencies such as longer-term periods, album commitments, and ancillary revenue participation, aka a ‘360 deal’.. yeah, I said it.

There are also ways for both parties to compromise, such as scaling back the royalty splits after a certain point. Let’s say the label provides $300k, all in, to an artist for the first album of a multi-album deal. Perhaps the label began by receiving 70% to 80% of the first album’s sound recording royalties. There are ways to negotiate the deal so that after, and if, the label recoups their investment, their percentage could drop to 60% to 70% on the second album, 50% to 60% on the third album, etc. Once you understand what's important to you, there are different ways to slice this pie. If you’re feeling spicy, as an artist, you could also try to negotiate copyright reversions if you’ve giving up ownership of your masters.

At the end of the day, this all goes back to the Operational Pillar. If someone asks for something, they should be able to prove why it makes sense - either based on their recent accomplishments, demonstrable data, or by presenting a plan that makes sense. I see some independent labels out here asking for master recording ownership, a high percentage of sound recording royalties, publishing participation, and show/endorsement money while not having the infrastructure or strategy to support their demands. That’s bad business.

LEGAL REGAL:

I’ve said it before, and I’ll say it again, ask any high-powered litigator; many of their cases, and much of their money comes from poorly executed contracts. Simply because either party didn’t want to do the work required (or pay a reputable lawyer) to properly negotiate their contract. While understanding and negotiating the operational and financial terms are key, the Legal Pillar gives the contract force, compels compliance, and provides for remedies if and when contractual obligations are not met. Here are a few clauses that are good to keep in mind:

Term

Simply put, how long does the contract last? This is important because many artists think because the A&R told them it’s a one or two-album deal that they’ll be out in a couple of years; meanwhile, the contract gives the label 4 options to pick up the artist for 4 additional albums. Keep in mind that each option can last up to 18 months, so you do the math. It’s important to model this out and understand how long you, as an artist, or as management for an artist, could be committing to in the deal. I would advise label owners here, but the contract often gives them the right to terminate anytime.

Another key point to note here is that there’s a difference between how long the artist will be exclusively signed to the label and how long the label has the exclusive right to collect the label’s share of royalties from the album (if they don’t own it). The first is the period of time during which an artist cannot have their music distributed by another company; the latter is self-explanatory, how long does the negotiated royalty share go to the applicable label? So on a three-year deal, with a 10-year retention period, it could look like this:

The artist signs in July 2023, and the deal runs through 2026, after which the artist can sign with another label, but the previous label has the right to collect their 50% to 80% until 2033.

Rights

This clause will determine whether the label owns the master recordings or is merely licensing them and for how long. This is simple to determine - as an artist, do you have the leverage to negotiate a licensing deal (e.g., the streams, clout, and data to tell a label - “you’re going to still make money if you only take 10% - 30% of my streaming income”)? As a label, think about what makes sense for the amount of money you’re willing to invest and the amount of work you think it will take to push the artist and see a return on your investment. Many people think all labels ask for ownership of masters, but many licensing deals are being done; they just don’t get publicized.

Release Commitment

A release commitment is a guarantee by a label that any required album will be released within a certain time period. This puts pressure on the label while providing assurances and clarity to the artist on what they can expect regarding album releases and contract length. This is a must to include in all recording agreements; most reasonable labels will agree.

Assignment

An assignment means to convey the rights to a contract to a third party. This is typically done when an artist signs to a production company (an independent label with limited resources) with the skill and experience to develop the artist and then “upstream” the artist to a major label to take advantage of the major’s distribution and marketing resources. The upside for the production company is that they retain certain rights to the artist (e.g. royalties) while partnering with a bigger company to help them increase the value of their royalties and income. The downside is that you have to split royalties, and perhaps other revenue streams with a third party. This is another reason why getting clear on the Operational Pillar is important. It might make sense to split the money three ways, but it might not, and if it doesn’t work out, what’s your recourse?

Right of First Refusal

You’ll often see this clause if a label is signing an artist to a minimal amount of albums. This clause creates flexibility for both parties while allowing the label to hedge its upside. For example, a label could sign an artist to a one-album deal; but stipulate that the label has the right to match any offer the artist receives after the initial deal (the one album). If the label puts out the album and it flops, they have the flexibility to let the artist walk, but if the album goes platinum; and the artist gets a big offer, then the label has the right to match the offer or let the artist walk. Everybody wins.

CONCLUSION:

“Look, I know killers, you no killer, huh

Bathing Ape, maybe, not a gorilla, huh

Glorified seat filler, huh

Stop walkin' around like y'all made Thriller, huh”Jay Z, ‘Moonlight’

There’s much more I could say, but I wanted to keep this general and show how straightforward this can be when you understand the questions you should be asking, and issues you should be spotting. Many of the frustrations from record deals come from unaligned expectations. In the law, there’s a concept called “meeting of the minds,” which means that both parties understood the terms of the deal and came to a common understanding. This is key. It doesn’t mean that everything will be cherry pie; it does mean that you’ve thoroughly accounted for the known variables before jumping into it and eliminated many problems before they occurred.

A business partnership is like a marriage; would you marry someone without asking them questions, meeting their family, understanding their background, seeing how they act in different situations, and figuring out how they will improve your life? Maybe some would, but I wouldn’t. It’s the same thing… many people let desperation drive their decision-making; it’s understandable, depending on where you are in life - but that’s why I’m here telling you this. Even if you have to agree to certain terms because of a lack of leverage, there are ways to build in contingencies for what happens if things work out well or don’t work out well; and anyone unwilling to negotiate on clear footing isn’t someone you want to do business with.

That’s how I think.

Why is this important? Because the music business is about hits and assets. Sure, music is a hobby and a form of expression; but the recorded music industry is about hits and assets. That’s the game, period. And if you don’t understand the rules, you will lose. Here are a few recent record label acquisitions

300 Entertainment acquired for $400 million

Quality Control acquired for $300 million

Big Machine acquired for $300 million

What do these labels have in common?

They all owned the masters.

Wow. Thank you for this in-depth piece!

Musical artists are effectively business owners. I learned the parlance of contracts over the decades by having to sign a lot of these types of agreements in order to do business, or to create new businesses and partnerships, but most folks have no idea what they're in for.